Saturday, February 4, 2012

Servante of Darkness #7: Zombies, Ghouls and Gods

Dead of Night (2011)

by Jonathan Maberry

Reviewed by Anthony Servante

Welcome back to the Servante of Darkness in this the month of February, the year 2012. Today we will discuss the thin line that separates life and death, and how the literature of Zombies blurs that line. We will distinguish living creatures from the living dead, and the mortal dead from the immortal. We will examine the nature of zombies under these criteria in "Dead of Night" the newest novel by Jonathan Maberry, and in "Carnage Road" also a new work by cult director/writer/webmaster Greg Lamberson. So, dear readers, let’s begin our journey down the River Styx. Don’t lose your return ticket.

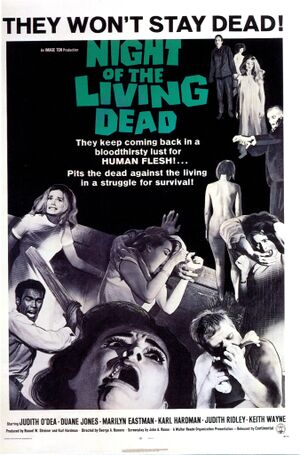

We can agree that George Romero’s "Night of the Living Dead" (1968) started what we call the 'Zombie Apocalypse' archetype of today. But before Romero’s zombies appeared on the screen, there were influences on the genre in literature and movies. While Hollywood was making “injuns” go woo-woo, and had white actors wearing blackface, it was also creating voodoo zombies. The Vodun (voodoo) religion teaches that there are spirits in all things, living and dead. But the corrupted interpretation of this spirituality focused on the living and dead being combined by use of white magic, or herbal potions, thus introducing the spirits of the plants to a living person to push aside his own spirit so that the new spirit could inhabit the host body. “All creation is considered divine and therefore contains the power of the divine. This is how medicines such as herbal remedies are understood, and explains the ubiquitous use of mundane objects in religious ritual. Voodoo talismans, called "fetishes", are objects such as statues or dried animal parts that are sold for their healing and spiritually rejuvenating properties. Sorcerers and sorceresses called Botono (or Aze/Azetos) are believed to cast spells on enemies on behalf of supplicants, calling upon spirits to bring misfortune or harm to a person or group” (wiki).

In "The Magic Island" (1929) by W.B. Seabrook, the voodoo zombie or host is introduced as a slave worker. A workforce of slaves who didn’t complain and weren’t paid was more a capitalist’s dream rather than the impetus for the creation of the zombie we know today. In the movie "White Zombie" (1932), Bela Lugosi plays Murder Legendre, a voodoo magician who tricks people into drinking a potion that turns them into zombies that serve his bidding as mindless but obedient slaves. In this sense, the victims were still alive with the “spirit” of the potion but acted dead because their own spirit was ousted, thereby making them easy to control by the magician, dark priest or witchdoctor. “Haitian zombies were once normal people, but underwent zombification by a "bokor" or voodoo sorcerer, through spell or potion. The victim becomes a mindless automaton, doomed to a life of miserable toil under the will of the zombie master” (wiki). Murder turns his rivals and other victims into mindless subservient hosts by having them drink the voodoo potion, but these living dead can be brought back to life when the host master is killed. Thus the white zombie can be revived and his spirit restored, giving Hollywood a means to a happy ending. We’ve come one step closer to Romero’s zombie. The hordes of hosts inhabited by voodoo spirits still needed to lose the capitalist leanings. They needed a good old invasion.

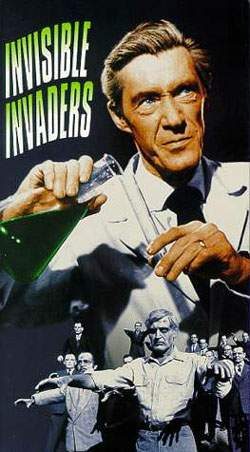

In the unfairly ignored movie "Invisible Invaders" (1959), invisible space phantoms inhabit the dead to take over the world and the first Romero-ish zombie was born.

Invaders captured the look we’ve come to know as a zombie today. No longer were they a working class but reanimated corpses with a malevolent purpose. Although the film is considered science fiction, it gave us the living dead look common to depictions in books and movies today. All that was missing was the appetite for human flesh.

Which brings us to the ghoul. “According to legend, ghouls are perceived to be unintelligent and are primarily driven by their instinct to feed. They are nocturnal because they prefer the night to disguise their cannibal activities” (wiki). These ghouls usually fed on recently buried bodies in graveyards and usually alone. “When discovered, they will usually hiss and growl to ward off intruders and, if that fails, they will attempt a quick escape. Ghouls will only fight if they are cornered, or if they outnumber the living by at least three to one odds” (wiki). In literature they are depicted as toothy human-like creatures, a cross between a jackal and human, according to Arabian folklore; they were shape-shifters, luring desert travelers into traps to devour them. The ghoul we Westerners have come to recognize, however, is more akin to Cousin Eerie from Warren Comics.

Note the disheveled appearance and toothy smile. So, now we have two elements that make up the modern zombie: the mindless malevolent dead with an appetite for living flesh and a pack-like behavior when attacking its prey. Combine a ghoul with a white zombie, and you’ve got Romero’s zombie.

Life is eating. We eat to survive. Why do the dead eat? Perhaps it is a conditioned response, as the undead in Romero’s "Dawn of the Dead" (1978) are conditioned consumers, mall shoppers. Zombies think they are still alive and follow their routines in the limited manner they were accustomed to, limited by their rotted bodies (the view extrapolated in Jonathan Maberry’s "Dead of Night", as we will see later). Another condition is animated life. Every action the undead makes and does is conditioned by “memories” or instincts to continue living unaware that they are dead. In this sense, they imitate pure instinctual life and exaggerate it. Eating is now devouring and gorging. And if live flesh is nourishment, it must follow that it gives them the energy to remain animated. But can a zombie starve and lose its animation, thus “dying” (if we can say a dead thing can die—the old vampire paradox, a cousin of the living dead). Eventually the corpse or corporeal being can eventually rot away, like leprosy, and the animation can eventually end. I asked Jonathan Maberry the question, “Are zombies mortal or immortal?” He answered, “In DEAD OF NIGHT and PATIENT ZERO, they are in the process of active decay--which is in keeping with how nature does things. So, eventually, they'd rot away and the plague would be over. In the ROT & RUIN series, the zoms stop rotting at a certain point --which is in keeping with George Romero--and it’s a mystery that no one can explain. Though...by the fourth book in the series, FIRE & ASH (due out in September 2013), I will provide an explanation.” So, the answer is yes and no. Zombies can die, but they can also live forever, in a relative sense, forever meaning as long as they have sustenance. I don’t want to conjecture about Maberry’s plan for the “immortal” zombie, but I can assume it has something to do with consumption. How many billions of living creatures are there on this Earth? Enough to sustain a zombie apocalypse? The zombie species is finite just as the living are finite, but here between life and death, the next step would naturally be the opposite of death—not life, but immortality. Which brings us to the gods.

The gods at various points in history represented various states of being or emotion or desire in many cultures. There was a god of love, of avarice, war, peace, life and death, and these gods were considered immortal; it wasn’t until the arrival of Christianity that the old gods were shelved and the One God took over. Then angels took on the duties of the former ‘gods’. Thus was born the Angel of Death, or the Grim Reaper. Death is a skeleton holding a scythe. They are lords of the underworld. Hell on earth. In "Dawn of the Dead", Peter, the National Guardsman, (played by genre cult actor Ken Foree) says, “When Hell is full, the dead shall walk the earth.”

This parallels the zombie who is skeletal and taking down lives with its insatiable hunger. Death is an angel whose touch is fatal. This parallels the witchdoctor who turns his victims into voodoo zombies. With zombies life and death are the same. So too with the gods who do not know death and live forever. Death is a creature with a life, but who doesn’t die—only consumes. He is immortal. He is not aware of his own death because he has none; zombies are not aware of death because they are lifeless, feral creatures animated by habits and customs they once were conditioned by in life. Zombies do not put the fear of hell in their living victims—they put the reality of death in their face; they know they will cease to be, eaten alive, or become one of them, the feral dead. Their victims do not fear death; they fear a living death, becoming the dead creatures that seek to eat them alive. Death creating death. How can they reach heaven if they never die? Forever dead.

With a nod to Prometheus Unbound, the story of a god—or as we know the story better as: Frankenstein, a story of how a man of hubris brought a collection of dead body parts reanimated to life. Here Mary Shelley’s monster is closer to god than the zombie of Romero. "Frankenstein" by Mary Shelley, while not a zombie novel proper, prefigures many 20th century ideas about zombies in that the resurrection of the dead is portrayed as a scientific process rather than a mystical one, and that the resurrected dead are degraded and more violent than their living selves” (wiki). There is a catalyst that animates the corpses, whether mystical or chemical, virus or evolution gone awry, to become a pack of feral humans, void of life, but exaggerative and animated in appetites and routines based on old memories like a broken vinyl record repeating itself as the phonograph needle bounces back and forth, replaying the same part of the song again and again, the zombies perhaps remembering family and family gatherings or concerts or sports events, and thereby flocking together. Ghouls are loners in their cannibalism and are neither godly or undead-ly. But as social zombies, they devour together.

Which brings us to the Zombie Apocalypse. “The zombie apocalypse is a particular scenario of apocalyptic fiction that customarily has a science fiction/horror rationale. In a zombie apocalypse, a widespread (usually global) rise of zombies hostile to human life engages in a general assault on civilization. Victims of zombies may become zombies themselves. This causes the outbreak to become an exponentially growing crisis: the spreading "zombie plague/virus" swamps normal military and law enforcement organizations, leading to the panicked collapse of civilian society until only isolated pockets of survivors remain, scavenging for food and supplies in a world reduced to a pre-industrial hostile wilderness” (wiki). The living seek immortality by becoming angels in heaven, while the zombies represent a corrupt immortality, living forever as dead creatures mocking life through conditioned exaggeration.

We need not discuss the various types of zombies, the fast, the slow, etc, as I prefer to focus on the life of the dead, per se. “[T]he most definitive "zombie-type" story in Lovecraft's oeuvre was 1921's Herbert West–Reanimator, which "helped define zombies in popular culture". This Frankenstein-inspired series featured Herbert West, a mad scientist who attempts to revive human corpses with mixed results. Notably, the resurrected dead are uncontrollable, mostly mute, primitive and extremely violent; though they are not referred to as zombies, their portrayal was prescient, anticipating the modern conception of zombies by several decades” (wiki). West sought god-like powers to control life and death, thus creating a model for the modern zombie we know today: an accident of nature or human hubris. Only now, the survivors strive to cheat life as the undead. They are evading immortality, cheated of heaven in the post-Romero apocalypse.

In "Dead of Night" by Maberry, his zombies take on the Frankenstein approach, man with hubris or bad intentions gone awry. The consequences of his god-like experimentation drive the story. Just as the white zombie represented the working stiff, so to speak, Maberry gives a nod to original version of the living dead. Hartnup, the first victim we meet, a mortician, describes the corpses he works on as “hollow people, empty of life” before introducing us to the catalyst for the apocalypse. T. S. Elliot’s poem, “the hollow men” represents the transition of the spirit from the body to heaven or hell, just as the voodoo victims had their souls displaced by a different soul via the witchdoctor’s potions. At ground zero of Maberry’s zombie apocalypse is a prison physician playing Frankenstein on a condemned serial killer with a potion meant to keep him alive mentally as his body decay six feet under. But this act of godly intervention creates the monster that breeds the plague of undead in typical hubris brought down by the mortal flaw; in this case, the prison doctor cannot anticipate the magnitude of his failure to achieve god-like status. Hartnup experiences the nightmare of zombie immortality as he himself becomes “a hollow man” that remains sentient. “How could he be dead… and know? He should be a corpse. Just that. Empty of life, devoid of all awareness and sensation.” The end is set in motion. And this is one of the most enjoyable things for me in the book—that beginning when we enter Hartnup’s narrative as he transforms; we sympathize, then empathize, and finally, while we think we see it coming, it’s too late, we feel for him. He’s become a major character we care for. Nice shooting, Mr. Maberry. Target acquired. The bar has been reset in the zombie genre.

We later learn that the “hollow man” that bit Hartnup was the murderer who “died” from the lethal injection on death row. He, too, was meant for death but was cursed with life in death because of the mishap with the potion that was intended to end his life, not renew it as the undead.

Desdemona Fox also has a literary allusion to life in death. In the Shakespeare play, OTHELLO, Desdemona is a character so devoted to her husband that even after he kills her; she awakes from death for a second to defend the man she loves, her murderer, before collapsing back into eternal sleep. It is no coincidence that Dez is the law enforcer standing between life and death, between the zombie rise and the fall of the living. In Othello, this separation of life from death is represented by dark and light. For Maberry darkness is the emptiness that represents the dead, the blackness that occupies the hollowness vacated by life.

The twist we get from these allusions is that we see Hartnup’s birth in death and his rebirth as a zombie, just as we see Stebbins County lose its light and go dark in the apocalypse. Maberry describes Hartnup’s unwanted immortality, “Hartnup begged God to let him die for real and for good and to not have to be a wintess to this [resurrection]”. And later: “He could feel everything. Every. Single. Thing. Jolts in his legs with each clumsy step. The protest of muscles as they fought the onset of rigor even as they lifted his arms and flexed his hands. The stretch of jaw muscles. The shuddering snap as his teeth clamped shut around the young police officer's throat. And then the blood...." Although the writing style may seem disjointed, it is intentional to capture the jerky moments of the zombie Hartnup. It is a clever device to advance the notion of life in death as we bear witness to the apocalypse through the mortician’s eyes, eyes long locked between hollow corpses and hallow men.

That is as far as I can take you on this journey from life to death and back again without spilling into the spoiler pot. It is best to read this fine novel to experience the trek oneself. Rest assured that Dead of Night not only advances the zombie lore beyond its traditional barriers but entertains us while taking us there. Jonathan Maberry has scripted the end of the world and has brought that hell on earth for us to witness from two points of view: life’s and death’s. This is as close to becoming a zombie as you’ll ever get and hope you never get.

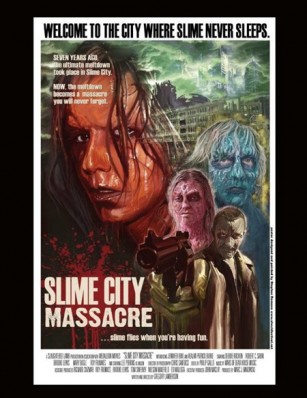

Carnage Road (2012) by Greg Lamberson

Reviewed by Anthony Servante

The name that keeps popping up in the CR reviews that I’ve read is Jack Kerouac and his book, ON THE ROAD. The 'Beat Generation' wrote about a rejection of materialism. The journey for Lamberson in his Zombie Apocalypse novel represents life as a voyage to death without the need for accumulating wealth or material weight by stopping and staying in any one place. To stop is to die. The term, Beat, is based on the term, “on the beat,” which itself means, bohemian or gypsy travel, surviving as opposed to living. And that’s what CR’s heroes do: survive.

For Kerouac, it meant not only survival but spontaneity. But for him it also meant a crossing over into spirituality. “Kerouac commented, 'On the Road' ‘was really a story about two Catholic buddies roaming the country in search of God. And we found him. I found him in the sky, in Market Street San Francisco (those 2 visions), and Dean (Neal) had God sweating out of his forehead all the way. THERE IS NO OTHER WAY OUT FOR THE HOLY MAN: HE MUST SWEAT FOR GOD. And once he has found Him, the Godhood of God is forever Established’” (wiki). I want to persue those allusions by following its Beat storyline. Life as a journey to death. The road of life leads to death. It is same path for both life and death.

The zombies in this tale are peripheral to the main characters; Boone and Walker are the last two members of the Floating Dragons motorcycle gang, splintered by rogue cops who kill half their biker club members. Our duo begins a cross-country odyssey cutting through the zombie apocalypse. It is not hard to imagine these bikers as stand-ins for Jack and Neal on the road. They avoid the cold, a symbol for death, and head for Hollywood and warmer climates, the symbol for life. Our travelers meet religious fanatics, thus echoing our earlier thesis that god or immortality is the common factor between the living, who seek an eternal heaven, and the dead who live death immortally. I asked Greg Lamberson, “Are zombies mortal or immortal?” He answered, “I would have to think that they eventually atrophy to the point of incapacity... but I'm no expert!” He is too modest. In two of the book’s best moments, there is a clever zombie mob and a game spotting undead Hollywood celebrities. I also loved the allegorical stand at the Alamo in Texas. How apropos.

His road trip is fun, just as the Beats celebrated non-conformity and carpe diem, an inside joke for a zombie novel wrung through Beat sensibilities. And his zombies are more monstrous without the burden of deeper meaning, although there are traces of depth with the various people our travelers meet on the road. But with this short novella, I must be careful not to give away too much.

An eye-opening beginning and a gut-wrenching ending, "Carnage Road" entertains with this straight-up gore-storm that is easy on the social commentary but rich in the culture of the 'Beat Generation'. "Carnage Road" will be released in April from Creeping Hemlock Press’ Print is Dead imprint. Visit Greg Lamberson at www.slimeguy.com for more information. He is the author of JOHNNY GRUESOME and CHEAP SCARES! LOW BUDGET HORROR FILMMAKERS SHARE THEIR SECRETS. He is also the director of the cult horror film SLIME CITY and SLIME CITY MASSACRE and the creator and editor of the popular horror entertainment website Fear Zone.

Well, dear readers, that ends the Zombie Apocalypse of Zombie reviews. I hope you were enlivened by it. Or at least not bored to death. Or maybe a bit of both? Until next month, this is the Servante of Darkness bidding adieu to his readers with a flick of the light switch. On or off is up to you.

--Anthony Servante

.gif)